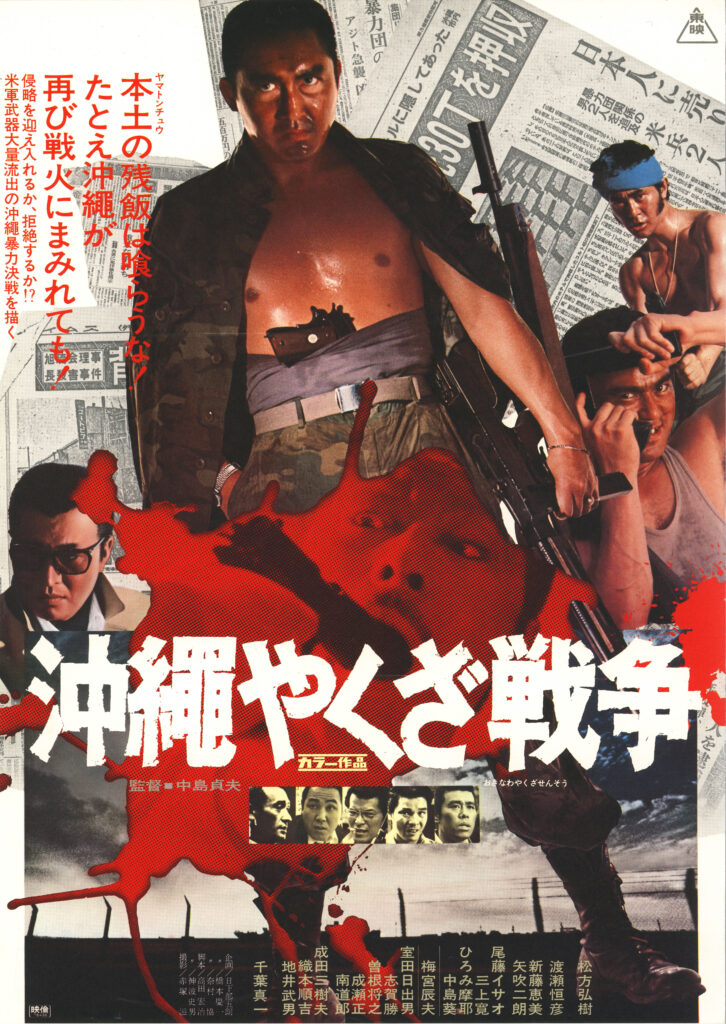

There must be a thousand Yakuza films floating around, largely forgotten and unseen (especially here in the US). Luckily, places like Tubi give you the chance to stumble upon these with pretty decent regularity (the same, I’ve realized, with jidaigeki/samurai movies as well). The Great Okinawa Yakuza War (aka Terror of Yakuza, aka Okinawa Yakuza War), with a top-billed Sonny Chiba in a supporting role that steals every scene he’s in, is one that really caught me by surprise. I expected something a bit rough, grainy, weathered by time and forgettable but worth a lazy Saturday afternoon watch. Instead, it’s a very personal tale about nativism and loyalty, their limits, and their self-destructive nature. Although it’s stuck in my head, it appears to have been largely forgotten, if it was ever even known.

Perhaps one piece that held it back was its score. In my limited viewing, I’ve noticed that a lot of more mainstream Yakuza films of the era tended to have sparsely used, unremarkable scores. Compare this with the wildness of a riskier Yakuza film like Tokyo Drifter or the music genre insanity of contemporary jidaigeki films like Lone Wolf and Cub or Samurai Reincarnation. Kenjirô Hirose’s score for The Great Okinawa Yakuza War unfortunately falls within the former camp.

The film begins with shots of sleezy neon, the vice-filled streets of Okinawa that have just been opened to mainland Japan. Hirose pairs this with a groovy, funky quarter of drum, bass, guitar, and brass, something equal parts cool and devious. It immediately sets the tone of the film: the characters and their crimes are going to be a bit slick and cool, like the Okinawa gangsters from Beat Kitano’s Boiling Point. Except, this isn’t what we get at all.

The film follows lead-gangster Nakazato (played by Hiroki Matsukata), fresh out of prison after having murdered two rival gang leaders, thereby unifying the gangs of Okinawa. Upon his release, he expects to control half of Naha, the second largest city on the island. Instead, he has nothing, left to worry about how he’ll even feed his men. Meanwhile, the Okinawan gang is splintering and the island faces invasion from the mainland, threatening to wrest control away from the natives. Hirose’s use of funk could work as a nice subversion, the irony of the lofty promises of being a gangster with the grim, pauper reality. But it’s seemingly played straight.

Instead, Hirose continues to repeat this cue (or variations thereof) throughout the film, and it forms the bulk of the score. It quickly becomes tiresome and distracting, particularly as the film drifts further and further from any hint of 70s’ glamor and excess. In doing so, it also detracts from the tragedy of Nakazato and Okinawa. Nakazato becomes increasingly desperate through the course of the film, realizing he’s been betrayed on all fronts and the life that was promised to him will never be (and was never going to). At the same time, Okinawa has just been handed to Japan and the island’s small, insular society and culture is soon to be changed forever (with Okinawans having no say in the matter). But the score never really makes time for this tragedy: the funk plays on while the streets fill with blood.