Purportedly inspired by films like 2001: A Space Odyssey, Rollerball director Norman Jewison decided to largely eschew an original score in favor of using classical music. The supposed reasoning was to prevent the sci-fi movie from feeling dated, thereby undermining its near-future setting. While effective to an extent (it’s impossible to avoid the clearly 70s style, architecture, and visuals), the choice has a far more profound effect.

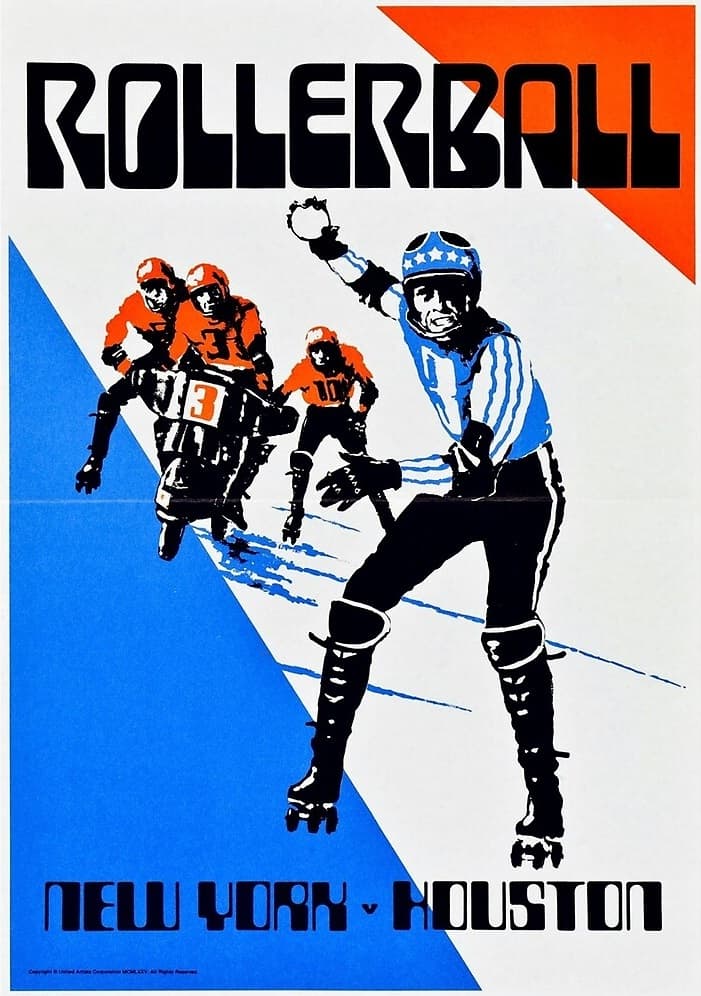

In Rollerball’s futuristic 2018, war, crime, poverty, and seemingly every other societal ailment is no more. Instead, the global populace has “rollerball,” a highly violent sport that seems to satiate humanity’s bloodlust. But it also helps create a neutered society, one in which the senses have dulled and culture has all but disappeared. It is such an extreme affliction that main character (and rollerball legend) Jonathan E. (played by James Caan) simply wants to feel something. This is the backdrop against which Jewison’s classical choices (conducted by André Previn, who also composed the brief score) play.

Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor opens the film, its death knell organ roaring over the start of a game of rollerball. This piece has a dual function: introducing us to the storm of violence and death that is rollerball, while also elevating it to society’s highest form of culture.

Rollerball’s cultural usurpation becomes more obvious as the film progresses. For instance, not long after the first game, Jonathan and his longtime friend and trainer Cletus reminisce, drink, and take drugs at Jonathan’s ranch. Classical music plays from the sound system. Cletus seems only capable of talking about past rollerball matches until Jonathan, losing interest, asks [paraphrasing]: “Where does this music come from?” It is almost unfathomable that this music could even exist in their world. Similarly, Jonathan and his teammate Moonpie visit a nearby library only to discover that books no longer exist – they’ve been replaced by heavily edited corporate summaries. The only copies are potentially located at secure sites run by controlling corporations. Of course, classical music ironically plays throughout this scene.

Even Previn’s short score follows this theme. His executive party cue appears during a massive soirée celebrating Jonathan. The music is funky and danceable, filled with slightly foreboding improvisational melodies. The party, meanwhile, is empty, languid hedonism, in stark contrast to the cue’s energy and liveliness. Through this juxtaposition, Previn draws further attention to the dull (if comfortable) status of society and Jonathan’s exhaustion with it all.

The commentary in Rollerball isn’t subtle. However, there’s a surprising depth to it, which the musical choices and Previn’s own score make deeper.