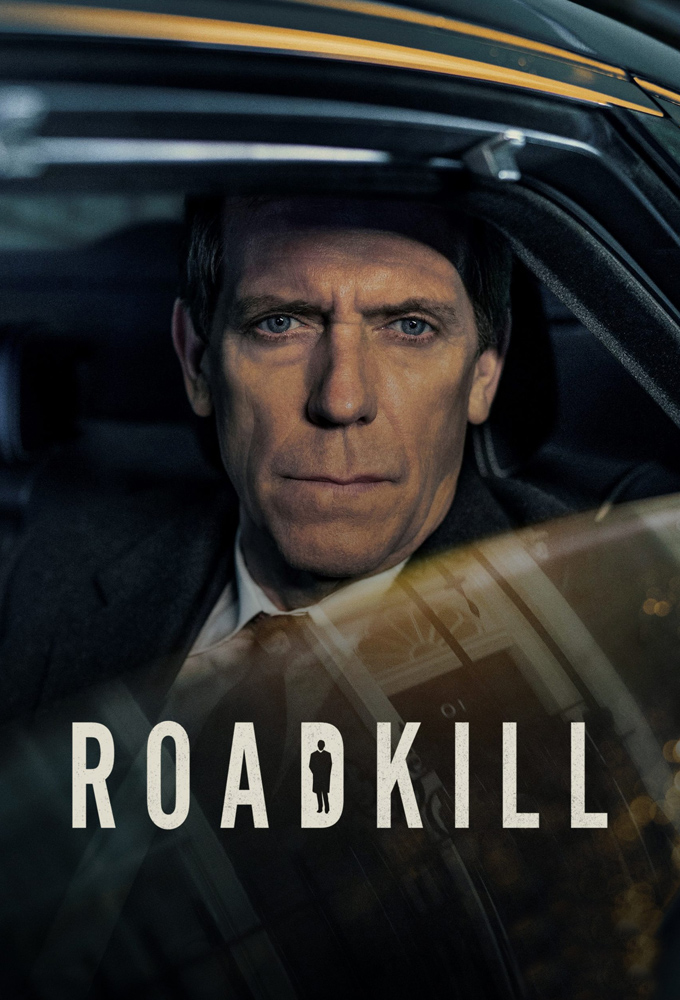

I caught up with composer Harry Escott to discuss his newest score: Roadkill. This is a new BBC One political drama starring the inimitable Hugh Laurie. You can find the whole interview: on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, YouTube, or right here on my site.

Before Roadkill, Escott seemed to have found his niche in the darker corners of the UK independent film scene. Among his works are numerous bleak films like Steve McQueen’s Shame, Paddy Considine’s Journeyman, and David Slade’s Hard Candy (among others). But Roadkill allowed Escott to do something a bit more mainstream and a bit less somber. The show follows Peter Laurence (Hugh Laurie), a Conservative MP battling through the cutthroat gauntlet of politics, often saved by his deviousness and penetrating charm.

The Sounds of Roadkill

On first listen, the music choice surprised me. I expected a much darker, more foreboding score, perhaps meant to replicate the chaos and discord so often associated with modern politics; I did not expect a suave, melodic jazz score.

“Laurence, he’s a sociopath really, he doesn’t care about the roadkill, he doesn’t care about the consequences of his actions at all, yet he’s sort of a very sophisticated, shiny character that’s kind of irritatingly likeable,” Escott said, “everything is really from his point of view . . . so the music is actually quite elegant and pretty and tuneful and melodic.”

Escott welcomed the opportunity for this approach, as it was such an about face from the scores he normally composes. Not only is the mood markedly different, but so is the composition style. Many of Escott’s past scores focused on lingering notes and droning textures (which he calls “stealth scoring”), creating broad shifting moods rather than melodic, noticeable themes.

“As a scorer if you’re not noticed that’s generally quite a good thing” Escott said. “The stuff I do, you don’t really want anyone to notice that you’ve done anything, you just want us to feel a bit uneasy or a bit sad. Whereas this is a completely different thing. It just deliberately has its own character and it’s deliberately quite a caricature, and it’s very stylized so it’s quite fun.”

Escott determined that a single instrument should be present throughout the score to match Laurence’s singular nature. Escott chose the piano because, like Laurence, it exudes a “classy” air. He then added a clarinet and drums for a full-bodied suave and sophisticated sound.

Escott admits that although Roadkill sounds new to many viewers, it isn’t. He intended the score to be a throwback to the 1970s, specifically mentioning David Shire’s work on The Conversation and All the President’s Men. These scores were particularly appealing not just for their style, but also for their inherent storytelling aspect.

Composing Jazz for the Screen

Perhaps the biggest challenge Escott faced when creating the score to Roadkill (other than working through fifty different themes before finding the right one) was composing jazz for the screen. Quite often, jazz is living and impromptu, whose players feed off the energy of one another as a session evolves. Rather than apply a proscriptive approach to this spontaneity and force it into the mold of a score, he embraced it. For instance, Escott and drummer Martin France sat in a room watching scenes, with France on the drum kit and Escott right behind him. As the show played, Escott audibly imitated the drum sounds and rhythms he wanted while France repeated them on the kit, adding his own flourishes and fills.

But the spontaneity wasn’t just a challenge – it presented new opportunities as well. “We’d record what I’d written and what I’d envisaged and then we’d do three or four wild takes and, invariably, something out of the wild takes was like ‘yeah that’s really much better than what I would have done.’”

A less obvious aspect that Escott enjoyed about the score was the effect it had on the musicians working with him. Although his scores are functionally effective within their respective films, he doesn’t always think they are “exciting” for the musicians to play. With Roadkill, however, Escott was excited to give these musicians “fun stuff they could really get their teeth into . . . and moments where they could just run with it and go and do some crazy stuff.”

It was clear listening to Escott talk that he loved the process as well, from writing for Hugh Laurie’s sociopathic character to jamming in a room full of jazz musicians. Eventually Escott revealed just how much he enjoyed it, reveling in the chance to play and be “a bit of a jazzer for a few months.” As a listener (and an interviewer), it was great fun for me as well!

Roadkill is available in the UK on BBC One and the US on PBS Masterpiece Theater. Escott’s score is forthcoming. Read more about Escott on his website.

Have a listen to our conversation below or wherever you get your podcasts (including Spotify and Apple Podcasts). Enjoying these interviews? Show the love by subscribing and leaving a rating or review!