Recent films like Warfare and shows like Adolescence (Interview) and The Pitt have got me thinking about the effectiveness of a lack of music. When something is shown in real time (e.g. Adolescence) or has a visceral immediacy (e.g. Warfare), no or minimal music can actually pull us closer to the “action”. Just as music can further immerse us into a project or make the artifice of moving images more obvious, so too can its omission.

Warfare is bookended by licensed songs, with no music in between. The film kicks off with the music video of Erik Prydz’s “Call on Me”, a poppy 2000s dance track whose video is oozing with sexuality. The crispness of the video eventually disappears, replaced by graininess of a deteriorated copy being shown on a weathered, older tv. A group of young American soldiers surround it, hooting and hollering, singing along, dancing. The film then hard cuts to those same soldiers in the streets of Iraqi city of Ramadi at night, carrying out a mission. While the music no longer plays, some of the soldiers still mime the music video’s overly-sexual moves.

As an aside, these two sequences display one of the discrepancies between co-director (and Iraq War veteran) Ray Mendoza’s comments and the film itself, which perhaps comes from the hand of co-director Alex Garland. Mendoza has mentioned that everything in the film happened (warped only by the passage of time’s effect on memory) and that the soldiers watching the music video showed their youth and immaturity as well as the lack of entertainment available on base. Perhaps true, but the segment in the streets takes this further, evidencing an unearned cocky confidence, a disregard of life and death. It’s reminiscent of Baby Invasion, where players dance and smoke among corpses or their kidnapped victims, all while an endless chat cheers them on from home. Whereas Burial’s score for Baby Invasion is pounding dance music largely meant to replicate what these players would be listening to while streaming, sitting us in their seat, music plays in the heads of Warfare’s soldiers as they’re about to imprison two families, steal their homes, and gun down Iraqis, only we’re one step removed and cannot hear it.

The lack of music for the next ~90 minutes places us in the moment of the action, the chaos. Filling the void are the banalities of a stakeout, the pummeling sound design of gunshots, explosions, cries of anguish. A score could bring us closer, but it could also create a distance. And of course, no score played on that day.

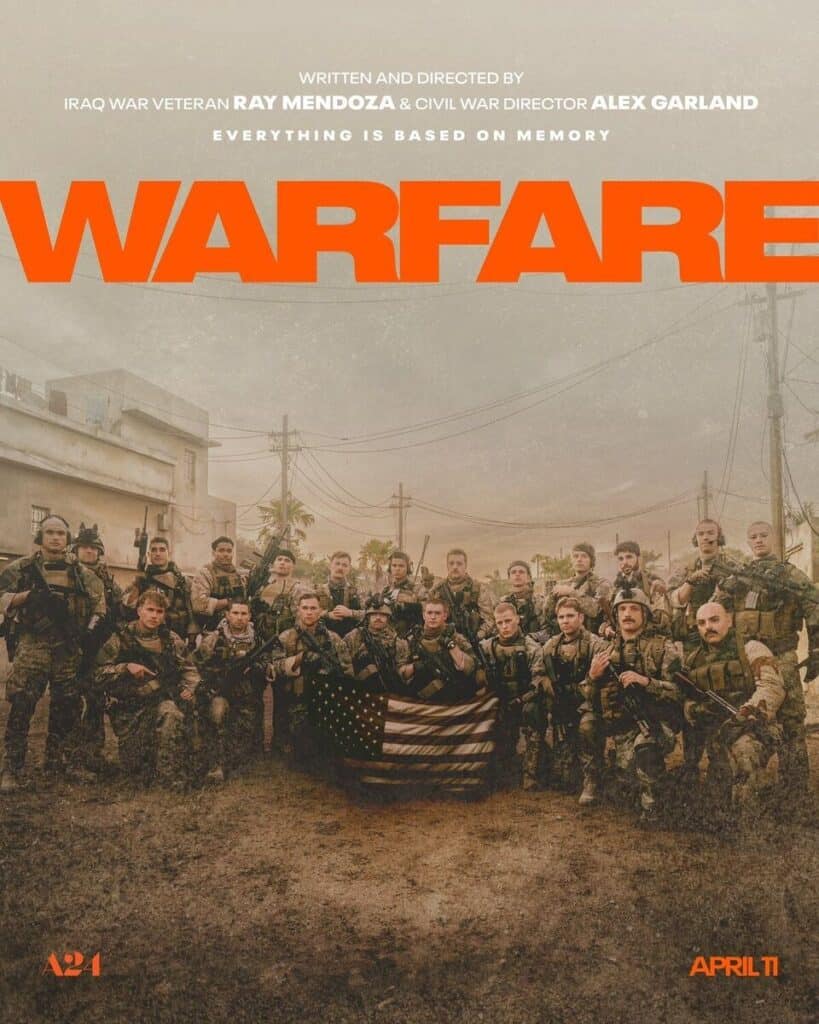

The next music comes at the film’s end, after the day’s events have ended but before the credits roll. A montage, of pictures of the actual soldiers (some faces blurred) and their actor counterparts, of the men on set, laughing, posing, hugging. Atop this plays Low’s “Dancing and Blood”, which serves as a pressure release unwinding the film’s tension and letting us breathe. It’s as if the music tells us that while what we saw may have happened, none of it was real, similar to the controlled exhilaration of a roller coaster, the excitement buttressed by the lack of any real danger.

The editing here is particularly impressive, with the end credits sequence starting the moment a tonal shift occurs in “Dancing and Blood”. For the entirety of the credits we hear two voices, one a constant drone that seems as if it’s continually rising in pitch and volume, like a Shepard tone for a single, sustained note. Accompanying this voice is something lower and primordial, calling up from the depths of the earth for a few seconds before disappearing. Is it a reminder that war is a constant specter, forever haunting us from the first days of our birth as a species?