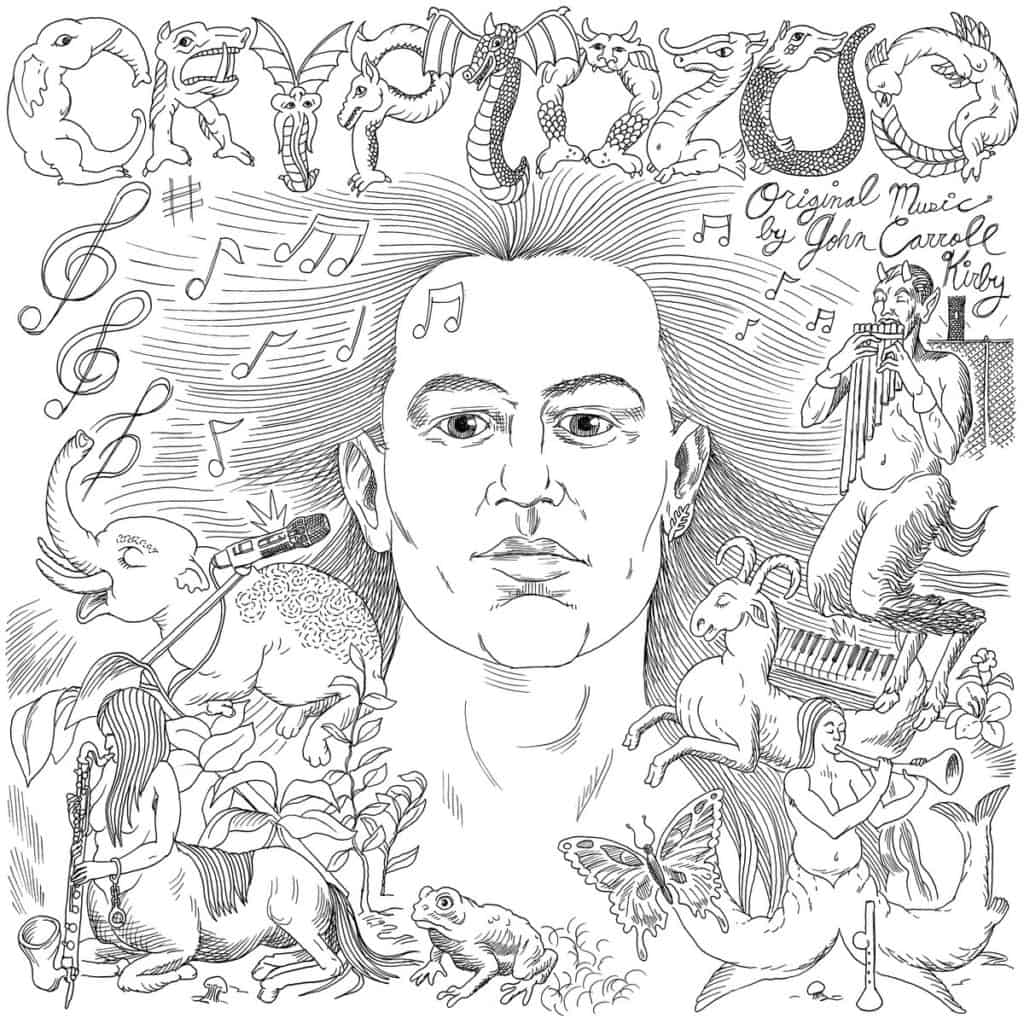

Not all films can live up to their premise. But at least in the case of Cryptozoo, John Carroll Kirby’s score does.

The animated film follows Lauren Grey, a veterinarian cryptozoologist, as she journeys across the world to try and capture a Baku, the Japanese folk creature that consumes dreams. Along the way we meet a number of other cryptids, some wild and others held on display at the cryptozoo at which Grey works (which may be turned into an amusement park at which the cryptids are forced to work, leading to some very obvious ethical calamities).

Cryptids, for those who don’t know, are animals that may exist. They’re often rooted in legend, folklore, and mythology, and include creatures like fauns, griffins, and imps. Cryptozoo employs a psychedelic, 60s/early 70s inspired art style through which these cryptids come to life in vibrant, expressive ways. But the film often falls into melodrama and an overlong focus on its human characters, distracting from the art and its beautiful creatures. There’s a promise of visionary imagination, but it’s never quite kept. This is where Kirby’s score comes in.

The composer and producer has worked in a variety of genres and collaborated with artists like Miley Cyrus, Frank Ocean, and Harry Styles. But Cryptozoo is his first score. Kirby applies his eclectic background here, mixing genres like new age, exotica, and early electronic with warm choral vocals, guitar, prominent bass, and even some pan flute. It’s genre transcendent. In doing so, it conjures something unexperienced. Though there are elements of familiarity, the end result is something completely new and unexpected. It pulls you into the world of Cryptozoo, forcing you to imagine and believe in an Earth actually full of cryptids. This then begs the question: what else is possible?

Tracks like “Phoebe’s Theme” have a warmth and almost childlike naivete to them, a dreamy, innocent nostalgia. They embed a false memory, of lying awake as a child, years ago, thinking about what’s real and what isn’t. This feeling riffs on Grey’s own fixation on cryptids from when she was a child and her lifelong goal of finding the mysterious Baku. But there is also a melancholic undercurrent, assuring us that this imaginary world cannot last, that it will be cast aside and scattered to distances unreachable. But that’s okay. Cryptozoo is a fleeting pleasure, a lesson in impermanence, a childhood dream that, once realized, we know must be released forever.

While Kirby’s score utilizes some thematic work, like the aforementioned “Phoebe’s Theme” or the recurring pan flute melody of Gustav the Faun, Kirby is more interested in the world of Cryptozoo. He brings these nonexistent creatures to life and makes us feel deeply sorrowful for them. Not just at their exploitation (both by those who know better and those who don’t care), but at the sheer brutality they face and they immeasurable sense of loss when these one-of-a-kind creatures are gone for good. Even if the film sometimes stalls or falters in summoning its visionary world, it sets the stage for Kirby’s score, one of the most exciting and unusual in quite some time. It’s no surprise that Cryptozoo became one of my favorite scores of 2021 (perhaps my favorite). Who doesn’t long to fall into dreams at will?

Editor’s Note: John Carroll Kirby’s Cryptozoo also appeared in our articles for the Best Film Scores of August 2021 and Best Film Scores of 2021.

2 thoughts on “Cryptozoo – John Carroll Kirby (2021)”

Comments are closed.