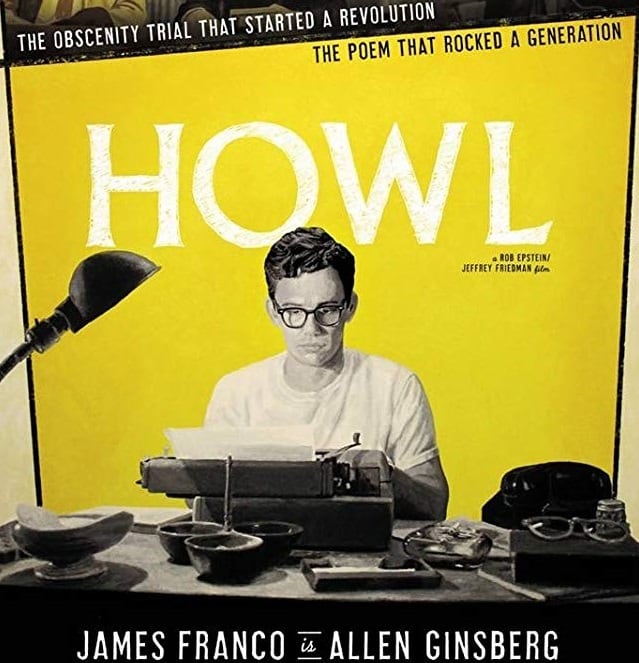

Howl is in many ways a cinematic ode to poetry. The film makes a deliberate choice as to when and whether to use music in its two portrayals of the titular poem. Allen Ginsberg’s public debut of “Howl” at the Six Gallery (as portrayed by James Franco) has no music. Instead, it is natural and realistic, supported by the background reactions of the crowd. In the other portrayal, Franco performs “Howl” in a voiceover while exquisite animations, which interpret the poem both literally and figuratively, take the forefront and are supported by Carter Burwell’s score.

The score is often quite restrained, acting in a true support role to Franco’s performance, avoiding any potential conflict between music and voice. As such it is minimal in its instrumentation, largely reliant on piano and strings, while jazzier sounds of upright bass and somber saxophone filter in, referencing the soundtrack of the Beat Generation.

Despite the relative simplicity, Burwell delivers an impressive tonal variety, often following the poem’s similar tonal labyrinth. The score moves between playfulness and an underlying darkness. These darker aspects, appearing most prominently, express themselves in various ways, such as through jazz-laden moments of overwhelming urban darkness, or slow, minimal interludes of synth, piano, and violin, creating a bleak emptiness. It eventually builds into the relentless battering of “Moloch!” before once again subsiding. Burwell’s score mirrors each of “Howl’s” ebbs and flows, peaks and troughs, adding to and amplifying it at each moment.