Clint Mansell has firmly established himself as one of the best film composers working today, so he doesn’t need to use gimmicks to draw interest to his music. But it’s easy to assume that by sampling the sounds of plants for his score to In the Earth, this is exactly what he’s doing. It isn’t.

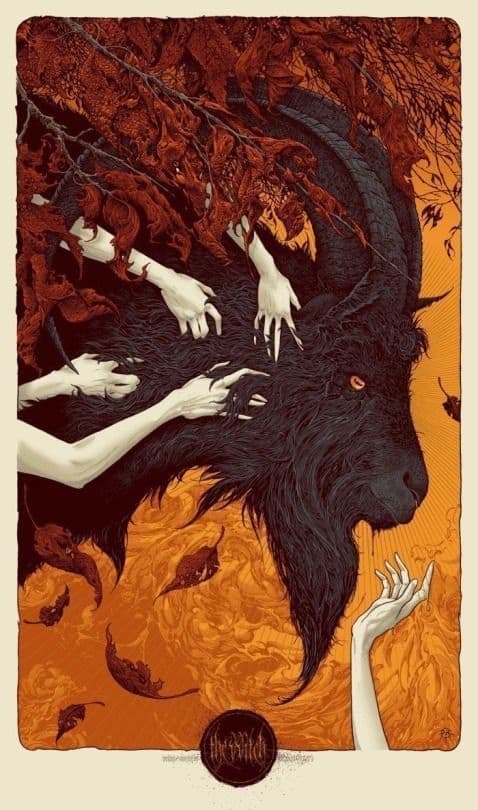

In In the Earth, a scientist and a park ranger travel deep into the woods outside of Bristol to search for a researcher, all while a mysterious disease ravages the country. On their journey they hear the local folk story of Parnag Fegg, a woodland spirit inhabiting (and ruling over) these woods. When they finally find the researcher, they discover she has been attempting to communicate with something in the earth, perhaps it is Parnag Fegg?

In the Earth is one of Mansell’s more electronic scores, but he approached it a little differently. Mansell actually used PlantWave – an instrument that translates plant biorhythms into MIDI – to capture the “singing” of plants and turn them into synthesizers and other electronic instruments and sounds. This was an important and inspired choice, because In the Earth is all about the conflict and tension between the natural and artificial worlds, between the earth and the people that inhabit it. By sampling plants, Mansell could create an almost all electronic score that nonetheless becomes a mixture of the organic and the synthetic. Rather than a more obvious choice, such as representing nature through something more “real,” like folk/acoustic instruments or an orchestra (akin to what Jerry Goldsmith did forty-five years ago in Logan’s Run), Mansell is able to represent both worlds while keeping a unified sound palette (although the track “In The Earth III” does introduce some acoustic guitar, with undulating electronics bubbling below).

But Mansell’s score is not simply a representation of the natural and human worlds. Instead, the unified palette touches upon the film’s theme of humanity returning to, and being consumed by, nature. Electronic sounds, distinctly human-made, become coopted by plants and this “haunted” forest. It’s subtle, and maybe too much so, but turns a gimmick into a statement.

Some of the score is, surprisingly, diegetic. The forest researcher, Wendle, attempts to speak to the forest using a big, noisy synth setup. With slow, amateurish notes she tries to speak. These appear in the three “Mycorrihza” tracks, becoming almost an homage to 60s/70s early ambient electronic experimentation. Wendle also records the sounds of the earth, completing the conversation in which Mansell, too, partakes.

The musical highpoints come during scenes of intense psychedelia. At times hallucinatory fits of vibrant, abstract imagery and strobing lights overwhelm the characters (and the audience). In these moments the film wages a war against humanity as the concepts of civilization break down into chaos. Mansell adds his own nightmare of noise and decay that straddles the lines of what could possibly be considered music. But these sequences aren’t simply the film’s highpoints, they’re arguably some of the best blends of pure imagery and music put to screen (like an amplified version of similar sequences in director Ben Wheatley’s earlier film A Field In England, with music by Jim Williams).

At one point in the film there is the line: “The forest is something we can sense, so it makes sense that we give it a face.” Mansell gives the forest a face, and it is frighteningly like our own.

Editor’s Note: In the Earth appeared in our best scores of April 2021 and best scores of 2021 lists.

3 thoughts on “In the Earth – Clint Mansell (2021)”

Comments are closed.