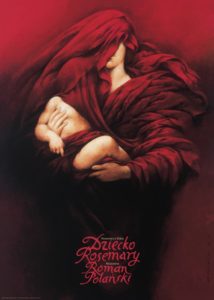

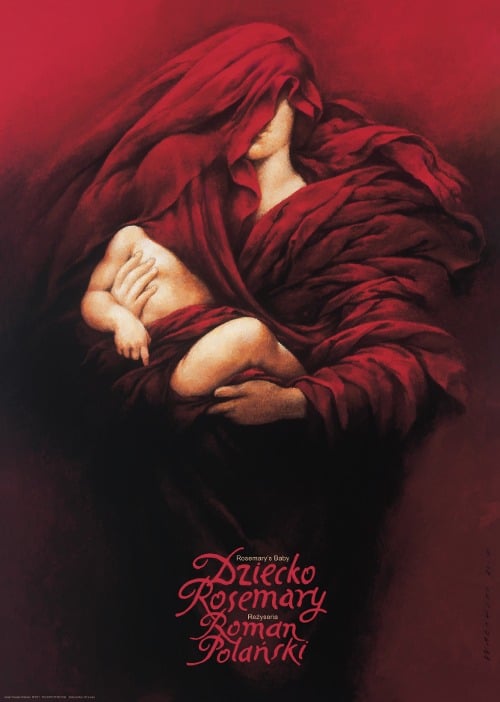

Krzysztof Komeda is considered the forefather of European jazz. And yet, his most famous and enduring work is the haunting and discomforting score for Roman Polanski’s horror classic Rosemary’s Baby.

The opening credits introduce Komeda’s single most well-known song – the “Lullaby.” The song actually progresses through seven different variants throughout Rosemary’s Baby, and if compiled into a single track would give the listener a near-complete version of the film’s beat points and plot. The initial variant uses dark piano and echoing harpsichord to disorient, while Mia Farrow’s repetitive half-singing floats over the top, nurturing yet sinister. While this version cues the audience to some unknown horrors to come, the subsequent variants celebrate every positive development in the life of Rosemary and her baby. They strip away the theme’s more ominous aspects as the piano melodies sweep optimistically, backed by warm and lingering violin notes.

These variants are intentionally disarming, and effectively so. The audience hears them and truly believes that maybe everything will be okay. This is all a ruse, however, and Komeda has made generations fearful of even the most innocent sounding lullabies.

Komeda’s distinct “European jazz” style is known in part for its ad-hoc improvising. This appears most clearly in the “Coven” progression of songs, particularly “Coven 2” and “More Panic.” These cues aimlessly meander, creating a dark atmosphere before suddenly bursting into painfully discordant violin crescendos like some sort of buzzing hive of horror and then once again withdrawing. These peaks and troughs are unexpected and unpredictable, adding to the sense of the unknown. This style has most recently been re-introduced through works such as Mica Levi’s ‘Under the Skin’ with chilling effectiveness.

Komeda also draws upon far more traditional jazz to further disarm in between these sinister, tense tracks. For instance, his sweeping piano and flute work on “Happy News,” coupled with Christmas-like bells, strikes an immense level of optimism, ensuring Rosemary and the audience that all is well.

The album also contains three additional songs not present in the film itself, all different variants on the lullaby theme. Most interestingly, they show how different an effect a melody can have based on varying instrumentation, pace, and intensity. The jazz vocal version is fun and fast paced, the complete inverse of the sinister theme, while “Composing 1” consists only of piano playing the melody, accompanied by an almost invisible breathy whistling, appropriate for an abandoned house filled only with mournful memories. They are neat extras that warrant a listen or two, but ultimately only serve to fill out what would otherwise be a brief thirty-three-minute score.

The score’s short length means that there isn’t music in every shot and instead gives room for the film’s natural sounds. A film that takes place in a massive city like New York already has a built-in score – police sirens, car horns, slamming doors, the rustling of feet. These noises naturally fill in the void that film music was originally introduced for, all without being overbearing. Komeda’s Rosemary’s Baby is one of the masterpieces of horror film music, made even more impressive given its brevity. As they say, “Hail Satan! Hail Rosemary!” and Hail Komeda.